|

| "Don't move until you see it." (credit to Joshua Waitskin) |

After a few microseconds of nostalgia, my mind raced to the question that I'm sure most people have the first time they see this game: "Does the dice 'popper' mechanism introduce any observable bias into the roll patterns?"

Now, for those that don't have experience with the game, it comes with a nifty little 'pop-o-matic' dice roller in the middle. Upon pushing this clear plastic half-hamster-ball bubble, the dice will rattle around a few times and then let you know how far to advance your pieces.

But there's the rub. To my eye, the dice didn't seem to have enough space to move around in the little bubble to sufficiently randomize each roll. So could this introduce some pattern to the supposedly random rolls?

To find out I recruited the nearest volunteer I could lay my grubby mitts on (my lovely wife) and had her 'roll' the dice a few times while I typed them into my computer. After a few rolls (185 to be exact... which reminds me I need to add another entry to the "I have the best wife in the world" list), it was time to do a bit of simple calculations. First let's look at the number of 1's, 2's, 3's etc... we rolled overall:

1 rolled 34 timesHmm.. looks pretty even to me. If we wanted, we could use some fancy statistics to give us a probability that this distribution of counts is 'uneven' but with the typical wagers made on a game of trouble being what they are ($0), we'll let it slide for now. And besides it makes intuitive sense that we don't see any biases showing up in these counts, as a symmetrical dice with any small amount of randomization should end up being pretty uniformly distributed.

2 rolled 32 times

3 rolled 27 times

4 rolled 35 times

5 rolled 25 times

6 rolled 32 times

But now we turn to the interesting story of second order interactions. And by that I mean: given that we start with (for example) a 6 showing, are we more likely to see certain faces on the next roll?

To investigate, I considered each observation in pairs (like 5 to 3, 3 to 6, ...), and then binned them into the 36 possible combinations (6*6). With this I obtained a matrix where the element in the first row and second column would be the number of times we saw a 1 and then a 2.

If you look at it for a second, something might jump out at you: There's a diagonal line of entries that are all significantly higher than the surrounding elements! Specifically, we see something like a 1 going to a 2 only twice, but we saw 13 1's rolling to a 6.5 2 5 3 6 13

3 5 5 6 7 5

3 4 2 11 2 5

6 6 9 6 4 4

5 10 3 3 1 3

11 5 3 6 5 2

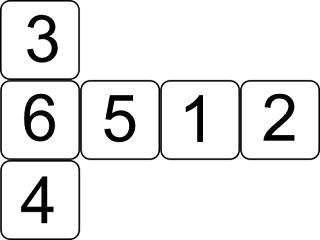

To explain this, I only need to show you one picture, a dice 'unrolled' (so punny) so you can see all the faces.

Don't move until you see it... (A classic inside joke from watching too much Chessmaster videos narrated by the wonderful Joshua Waitskin). Notice how the 1 and the 6 are on opposite sides of the die, and so are the 3,4 and 2,5 pairs. And notice how these are the exact same pairs that are over represented in our sample! So this leads evidence to the theory that the popper tends to flip the dice over in a better than chance way.

So next time you play Trouble, you'll have to decide whether to tell everybody this trick in the spirit of good sportsmanship, or to keep it to yourself and go on to wipe out Grandma's life savings in your ruthless ploy of statistically biased, high stakes Trouble.

Appendix 1: And I must say, I feel slightly proud, because a little bit of light Googling turned up nothing in regards to this bias, so I may very well be the first person on the entire internet to have documented it... or more likely: I simply didn't exercise enough Google-fu to find it.

Appendix 2: If you want the data, then say no more: '15264425415362261611516125166443431234131525646324116165231641523346213413545111466224436542365144532265251616362616443364434526132522342556143432242161165242434252413461634534352156162' although I warn you that there were some unobserved rolls by the interruption of a certain curious 3 year old. If you want the code, then let me know, but it is only about six lines of Julia.

Appendix 3: Bonus points, fit these observations to a Markov chain model to use in your next game with Grandma.